Stories from Around the Table | Teacher Rachel Sauvola

By Evyn Appel, NFSN Policy Intern

In 2022, National Farm to School Network and our partner organizations launched the “Who’s at the Table” campaign to raise awareness about the importance of values-aligned school meals for all policies (also referred to as universal meals). This interview series features the stories of real individuals who play a role getting food from the farm to school cafeterias. We looked into the lives of people who identify as a policymaker, principal, school nutrition supervisor, teacher, parent, student, and food producer from states with universal meals policies or states with strong coalitions still advocating for a policy.

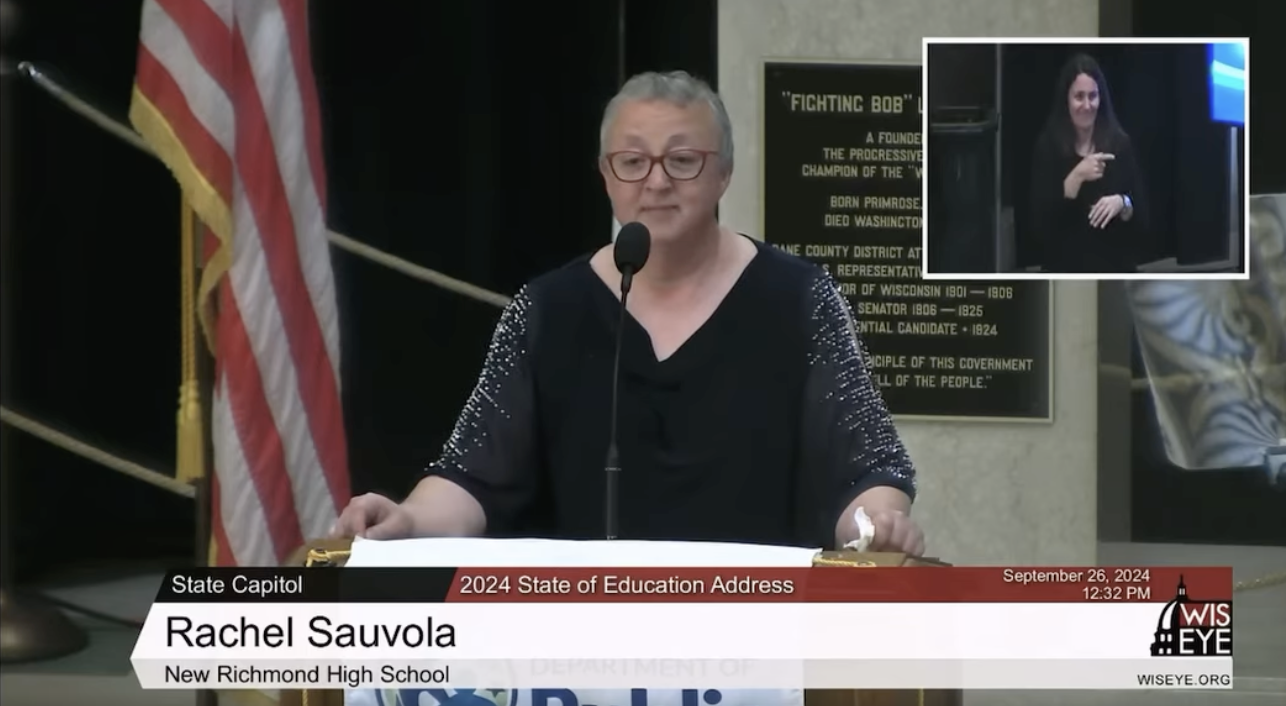

Teacher Rachel Sauvola (WI)

Rachel is an agriscience instructor and Future Farmers of America (FFA) advisor at New Richmond High School where she has taught and inspired students for the past 26 years. In addition to her classroom commitments, Rachel founded the Student Opportunities with Agricultural Resources (SOAR) educational center for the schools that serves as a year-round working farm producing cattle, eggs, honey, and vegetables to fuel school meals with local, student-raised ingredients. While Wisconsin does not yet have a universal meals policy, Rachel advocates alongside Healthy School Meals for All Wisconsin, a robust and energized coalition shaping future policies to expand school meal access.

We found Rachel after she was awarded the honor of Wisconsin’s 2025 Teacher of the Year. Her passionate acceptance speech focused on school meals for all. Here are just a few standouts from her remarks:

“Every single teacher I know has a drawer of granola bars. That may sound wholesome, but it isn’t. I have one colleague who spends over $60 a week of their own money just for snacks for her high school students. Now we know that high schoolers can be ravenous. But this goes beyond that. You see, in my district, elementary kids were so hungry, they were going into other kid’s lockers to steal snacks.”

“I don’t have to imagine, because I was one of those hungry kids…. I know a thing or two about hunger, and about how we stigmatize it. And we blame folks just for being hungry. That’s one of the reasons I became an agriculture teacher. After my first national FFA meeting at age 12, I was hooked. I made the connection between being able to grow food, feeding hungry people, showing leadership, and having fun while doing it. I was determined to break the cycle of hunger.”

“Giving every student access to free, healthy breakfast and lunch eliminates the stigma of getting free school meals. And let me tell you, our cafeteria makes all of our food from scratch, and it’s good.”

“It’s pretty simple. Good people don’t want children to go hungry. Good people don’t look at those that have less and think those people are worth less. And I will always, always choose to feed and value all children. In education, we talk about equity and inclusion. This approach walks the walk. Poverty is not a moral failing. Not helping those with fewer resources is a moral failing. And doubly so for those who have no say in the matter.”

Our Interview with Rachel

Q: Thinking back to picking a career path, what motivated and inspired you to be a teacher, specifically in agriscience?

Rachel: When I was 12, I told my dad, a Wisconsin dairy farmer, that I was never going to be involved in agriculture. I told him I was never going to marry a farmer, and never have any sort of career involving agriculture because it was too hard. Well, fast forward about 6 months, I went to my first FFA conference where I decided that I was going to be an agriculture teacher and FFA advisor. Quite honestly, I was a first generation college kid, but I embarked on that journey and with a whole lot of help and support actually from my agriculture teacher, I've never veered off the path. You can never say never!

The importance of the work, and quite honestly, the cute cuddly, one-day old baby calves, they make you just want to be able to offer that to others in a community where many don't understand how food is produced, and that's kind of my job. So I do it, and I love it.

Q: What does lunch time look like for the students of New Richmond High School?

Rachel: I'm going to tell you that lunch lines are long and our kids love the food. And one of the reasons why our kids love it is because we’re making things from scratch, developing recipes, and getting kid’s feedback. The kids will actually look at the menu, see if any SOAR center beef is on the menu, knowing that any hamburger products, any roast type products, all are coming from us, and the kids just love that.

But, moreover, after our amount of beef is used up, because I'm not to the capacity where I can produce it for the whole school year, I have connected our school nutrition supervisor with local farmers who are producing delicious high quality products. Our students are never eating big box beef. In general, it's mostly all coming from local producers.

Q: We often see the higher cost of local products being a barrier for other schools, how have you navigated that aspect?

Rachel: Our wonderful nutrition supervisor here at New Richmond is very creative in the means, but is also very honest when we negotiate our deals for prices at the beginning of the school year. She tells me “I can't pay as much as the general public.” But to me, it's irrelevant. I want the beef to come into the school, and I will take what she can afford to pay, and my farmer friends are in that same boat. They will take more from other places to get this opportunity out there for our kids to be able to eat this local nutritious food.

And likewise, when the folks from the community come to our steak sale next week, they are willing to pay a little bit over what they might pay at the grocery store. They know all the money goes back into the program. They know that they're bringing their family the most nutritious beef that they can find in our community. There is no fresher product out there and that's something people celebrate as well.

Q: Even though Wisconsin has a strong coalition of supporters for school meals for all, it has yet to pass a policy. What would having universal meals mean to you and your students?

Rachel: Well, I was one of those kids that could have benefited from universal school meals. And now that I have the means, and I have the voice, and I have the life experiences, it's my job to advocate for kids who have less than what they should have. But at the base level, kids cannot learn if they don't have their basic needs met, and one of those certainly is food in their belly. Student’s tummies are grumbling, they can't concentrate, they have anxiety because they don't know where their next meal is coming from. Goodness, gravy! Let's take care of business and feed the children so that we can be producing productive citizens who have goals and plans so that our society can move forward!

We have a family here in town who missed qualifying [for free meals] by $1.57. That's it, $1.57 in over the annual income limit. And now those students in that family are potentially not able to eat because they missed it. And [the student is] not at fault. They don't control the $1.57. They don't control the money that's put in their lunch account. They are just kids coming to school to learn and deserve to have food. If we could eliminate that barrier and just make it equitable for all, it would be such an incredible thing for our kids in all of our schools.

The SOAR Center always has a door open to visitors who want to learn more about the program and meet the students. To date, the SOAR center has welcomed visitors from 24 different states and 13 foreign countries.

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)